These are my notes on domain driven design whilst watching the course by Dino Esposito on Pluralsight.

Domain Driven Design (or DDD), is the process of discovering both data and behavioural requirements for a given problem domain where traditional approaches usually focus purely on data collection aspects. The aim is to provide better tools to tackle the complexity at the heart of software.

Within DDD, there are two distinct parts: an analytical one and a strategical one. To use a DDD centric approach, the analytical aspects are required while the strategical aspects can take one of many forms depending on the requirements gained from analytical insight.

Analytical

The analytical aspect of DDD is useful for everyone and every project undertaken because it describes the domain in which you are working, using a common set of language. The common set of language used is called ubiquitous language within DDD jargon. These aspects of DDD are key in a couple of main areas:

- When there is a lot of domain logic that can be tricky to digest:

- No synonyms for same/similar concepts;

- Ensures all terms are understood

- Or, the business logic is not completely defined:

- Business is young (eg: startup);

- Logic is discovered on the way

Ubiquitous Language

The aim of ubiquitous language is to avoid misunderstandings and assumptions by creating business centric terminology shared by all members of a project, both technical and non-technical. Once defined, the language should used universally in spoken and written communication, avoiding synonym creation which breeds ambiguity and misunderstanding.

Ubiquitous language is itteratively composed throughout interviews and brainstorming sessions using the natural language of the business, not creating new expressions for pre-existing concepts. The language will continually evolve over time, so it is important that updates are communicated across the business to reflect the understanding of the domain. It should neither be purely from domain experts nor technical experts. However, the ubiquitous language may contain some technical language to ensure clarity and consistency.

Acronyms are widely used across many business sectors that are hard to remember and understand. Where possible, acronyms should be avoided, being replaced by words that retain the same meaning of the acronym. This makes the language easier to use and understand for all parties involved. The language, although continually evolving, should not be continuly stretched as this will create a bloated, less regirous language than intended.

Lastly, the language used should be agnostic to all technology and paradigms. Moreover, when naming elements of code, the names should be reflective of the language used ensuring that concepts above are adhered to (eg: no acronyms/no synonyms).

Bounded Contexts

Bounded contexts are areas of the domain in which an element has a unique, unambiguous, well-defined meaning. Outside the boundries of a given bounded context, the ubiquitous language changes. If the meaning behind the language is same, the context should be the same. Each bounded context may have it’s own unique architecture and implementation. Moreover, each bounded context should have a well defined external interface so that it can be consumed from other bounded contexts.

This concept was introduced into DDD to help with the following problems:

- Remove ambiguity and duplication from within ubiquitous language;

- Simplify design of software modules;

- Help to integrate legacy software tools and components.

Within a given business domain, you may often find that the same term is used but with different meanings. When this occurs, it is a signal that the business domain should be split into multiple bounded contexts. However, these new contexts are not completely isolated as they are often connected through the way they communicate and interact with one another. Typically, the number of bounded contexts often reflects the physical organisation/department structure of the business.

Context Maps

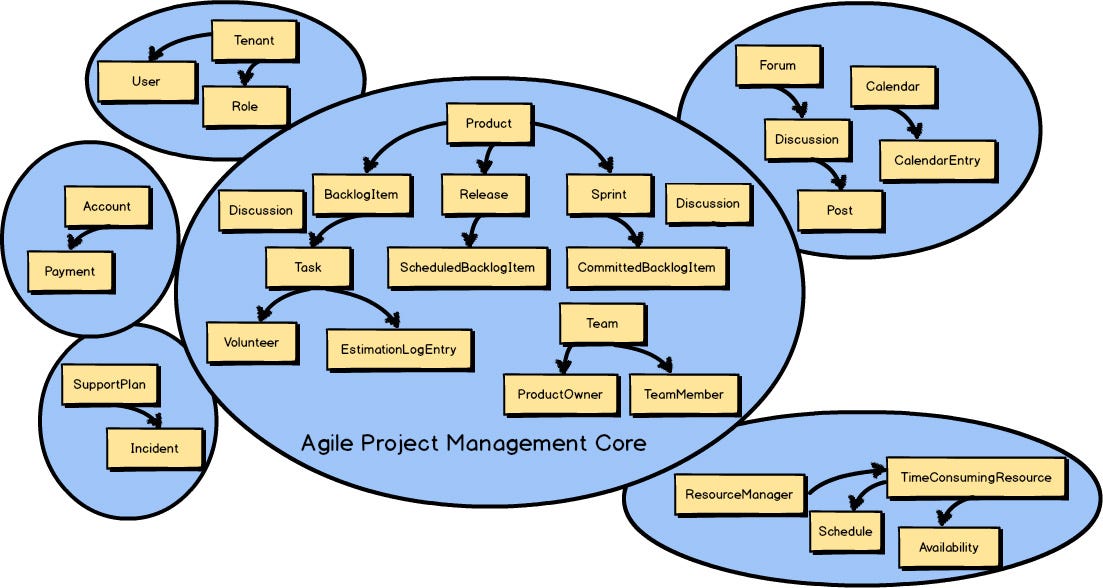

The overall layout of bounded contexts within a business domain can be represented on a context map, as shown below:

On the image above, there are a few new terms to understand:

- U & D or Upstream/Downstream:

- Upstream/Downstream shows the direction of the relationship between bounded contexts

- Upstream influences downstreams context and is available as a reference to the downstream context

- Downstream is simply a consumer of the upstream context but cannot influence it’s work directly (eg: change composition)

- Conformist:

- Indicates that the downstream context completely depends on the upstream context (eg: when the upstream context is a legacy system/external service)

- Typically no neogation of changes is possible

- Customer/Supplier:

- Indicates that the downstream context is dependent on the upstream context

- Negotiation of changes between the customer/supplier is possible and the customer can usually expect the changes to be made in some way

- Partner:

- Indicates a mutual dependency between two bounded contexts

- Changes are negotiated between both teams

- ACL or Anti-Corruption Layer:

- Fixed contract at the boundry of the bounded context

- Allows for internal changes without affecting consumers; so is most helpful when dealing with external API’s

Event Storming

Event Storming, originally developed by Alberto Brandolini, is an emerging practise to explore the business domain and identify key events and commands. The practise involves getting technical and domain experts together in a room to build a timeline of events and commands, draw sketches and make notes which helps to result in the following: - Comprehensive vision of the business domain - Identification of bounded contexts and aggregates in each context - Types of users in the system (who runs commands and why) - Identification of where UX is critical

Usually, a long whiteboard is used to note down the observable events on the time line, ideally with colour identification (eg: sticky notes). With coloured sticky notes, you would typically have a single colour for events and a different colour for commands (etc). This aids in the visual representation of the domain and the flows throughout.

The number of people in the meeting, should ideally not break the two pizza rule. The meeting should be kept on track through the presence of a facilitator, whos job it is to prevent long running discussions and guides the modeling effort. The facilitator doesn’t necessarily have to be a domain expert but this might be useful to get the meeting started.

Two pizza rule: Never have a meeting where two pizzas couldn’t feed the entire group